This is the full transcript of a piece I did for Kolkata-based magazine Good News Tab on literary-to-cinema adaptations; with a special focus on the Academy Awards and big-scorer, Ang Lee's Life of Pi.

---

The most recent film by Ang Lee, Life of Pi, is the film of a believer.

Adapted from an early 00s book (a literary sensation, a prize-winner) of the

same name by Yann Martel, it’s the sort of film which was, for the last ten

years or so, as close to getting made as it was to not – several directors were

attached to the project, several writers were hired to do drafts, several

actors were cast (and even as much as shot their scenes), but much like the

journey of the protagonist in the book/film itself, the project didn’t seem any closer to a finish. One could locate

interesting parallels between the legendary journeys (journey; that great narrative trope which allows for physical as

well as spiritual dislocation) undertaken by the book/film’s hero,

Pi-the-sailorman and studio executive Elizabeth Gabler, who through this decade

of uncertainty, kept hopes of an eventual adaptation alive. One could extend

this analogy further and claim that the production of a film, any film is as much a question of faith

as it is of a reason, as much a question of belief as it of pragmatism – like

the journey of Pi, the effort involved in finishing a film is a theological

epic in itself. And in this case, there are gold coins at the end of both the

rainbows: Pi discovers God, Gabler’s film has eleven Oscar nominations.

But then again, Life of Pi is the sort of film the Academy likes. The eighty-five year old institution likes

what most eighty-five year olds like: pleasant, comforting grand tales that

reassure them of a world full of optimism, generosity of spirit and eventually,

light-at-the-end-of-all-tunnels. It is a world where bleak caste and

race-related issues disappear entirely or atleast, by the time the film ends,

resolve their personal issues amicably. The Academy also doesn’t like films

that provide showboating opportunities for a single guy – a film shouldn’t be

imbued with the personality of a single star-director, so too much auteurism and what-not is a big no;

instead, the institution prefers films which provide a fertile ground for the visible

convocation of diverse talent. The film, in order to score big at the Oscars,

must feature evidently great cinematography, dialogue that is replete with

scene-ending one-liners and majestic monologues, gut-wrenching performances and

a story that traverses generations, if not eras. The Academy likes it if it can

feel that a lot of people have worked

on the film together – the winner of the Best Film at the end should seem like

a summation of the night’s ceremony, of all the awarded categories put into a

mix that then yields this one single

film. Consider this, in the recent past (sample size: last 20 years) films that

have won the Best Film trophy include: Slumdog

Millionaire (2008), Million Dollar

Baby (2004), The Lord of the Rings:

The Return of the King (2003), A

Beautiful Mind (2001), The English

Patient (1996), Forrest Gump

(1994), Schindler’s List (1993), The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

All of these films essentially function on the

same performative scale or exist, as it is, on an altogether consistent plane;

they feature an overarching evolving narrative, an intriguing premise, a lead

protagonist who must undertake an arduous journey (and in the process of

reaching his destination, indulge in self-discovery) and a grand hokey

statement at the end. Apart from these macro-level systems, most of them also

share micro-level similarities: large ensemble casts populated by a just

proportion of known and unknown faces, a socio-political debate (gender

politics, disability, euthanasia, disease, poverty; all covered) and a story

that is narrated through a very literary framing device: the flashback (one

guy’s the ancient mariner, the second the poet) . Now, the reason a film like Life of Pi may very well make it at the

Academy is because it does not in any way subvert this trend, if anything, it

extends it. But that’s fine, not every film or work of art should be a gesture

in subversion, to be able to expand a tradition or consummate its promise is in

and by itself, a noble aim. And Life of

Pi achieves this – it is nothing new and yet, in whatever it does that is

old, it is very good. What may also work in the favour of Pi is that, just like all the titles in the long-list above, it is

the adaptation of a literary work into the cinema.

Literature and cinema share a peculiar;

part-paradoxical, part-synchronous, part-filial relationship, the first being an

ancient artform, unalterable and permanent, ink impressed firmly onto the page,

that is thought to have reached the end of a period in the first quarter of the

20th century – this is around the same time when cinema would begin

to take its first steps as a medium capable of specificity (that is, a unique existence, torn from its aesthetic

predecessors in painting, photography and literature, free of loans or debts).

A number of commentators around the same time would begin pondering over this

matter and contemplate the question of cinema’s existence as a medium capable

of its own grammar, its own idioms and through these, its own expression. In

her 1925 essay on the cinema entitled, quite simply, The Cinema, author Virginia Woolf observed, ‘For instance, at a performance of Dr. Caligari (author’s note: a 1919 classic of the cinema) the

other day a shadow shaped like a tadpole suddenly appeared at one corner of the

screen. It swelled to an immense size, quivered, bulged, and sank back again

into nonentity. For a moment it seemed to embody some monstrous diseased

imagination of the lunatic's brain. For a moment it seemed as if thought could

be conveyed by shape more effectively than by words. The monstrous quivering

tadpole seemed to be fear itself, and not the statement 'I am afraid'.’

One may say that this is a

rather simplistic resolution of the crisis, of the constant tug-of-war between

the two media – and yet, for the year of its publication, it is rather

remarkable. It is also not entirely false to claim that if anything, film has

still not severed entirely its ties with literature – that images all over the

world are still employed merely to illustrate text and to only be vehicles of

meaning that are propelled, still, by words themselves. Insofar as one may

think that cinema’s great ambition should be to tell its stories through only

the visible – through visuals, pictures,

photos, stills, slideshows, frames, illustrations – and in the case of Life of Pi, through computer-generated

imagery, the film exists as an interesting prototype of the crucial differences

between the two human forms of art. It frames its story familiarly – one dude

with a writer’s block goes to another mysterious guy (Irrfan Khan, grappling in

equal measures with an unimportant role and with English) and asks him to tell

him this great story that he has heard somewhere he can tell – the second guy

launches into an epic flashback which forms the central narrative of the film.

This, as one may recall, is

very similar to another film made by a foreign big-name director in India that

scored huge at the Oscars; 2008’s Slumdog

Millionaire. In that film, our lead protagonist appears on a quiz-show and

answers each question with extreme dexterity – but this is only a

structural-ruse. Actually, each question’s like a portal into his past. We know

as an audience that this guy’s only a tea-seller (with impeccable English), so

how does he know all these answers? The film volunteers that each question he

is asked relates somehow to an incident from his past life, the experience of

which he summons to respond to the question. The film is told, therefore,

almost entirely in a series of flashbacks and a series of very freaky

co-incidences. It is also a great picaresque story, an ode to street-smartness

and the virtue of experience – if

anyone ever needs to make a case for the street-smart hustlers over the

bookworms, this film’s on their team. More crucially to our present discussion,

this film too, like Life of Pi, is

based on a book: author Vikas Swaroop’s best-seller, Q & A. But there are other similarities in these two Irrfan

Khan starrers: in both the films, the sequences which feature wordy tracts,

conversations, dialogue exchanges, voiceovers or narrations weigh heavily onto

the film. They are heavy-handed, badly played (in no less reason because of the

discomfort of most Indian actors with English) and staged unimaginatively. On

the other hand, scenes that contain portions of visual splendor and

screensaver-beauty (or oddness) are handled with much caution, crafted

meticulously and presented with much fervor. This is especially the case with Life of Pi, where the narrative travels

back and forth between scenes of the teenager-Pie, shipwrecked in middle of the

vast illuminated ocean, stranded on a boat with a CGI tiger and middle-aged

Pie, sitting in an average American-living room, living out his life as an

average dad of two, husband of one.

One may argue that this

contrast is pertinent to the whole idea of the film – that in order to reach a

position of eminent and comfortable, almost dull stability in life, this

character has to first undergo an arduous journey – but that belies the great

proven truth about cinema – great directors can make sequences of ordinariness

look spectacular. It’s interesting that when he started out in Taiwan, these

chamber-drama types set inside modern tract houses was director Ang Lee’s

specialty as well; this is before he moved on to awesome, outwardly spectacular

films that eventually made him famous (starting with, perhaps, 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). By the

time he directs Life of Pi, Lee now

spends his skill as a visual stylist entirely on sequences set in the outdoors,

in the great open sea – this, he achieves through clever variations in aspect

ratios (like a guitarist alternating between effects/ sounds/amplifications,

Lee alternates between square and rectangular formats), colour temperatures of

his images (the sea is sometimes a honey-coloured warm glow, sometimes a

turquoise), emphatic special-effects (the sequence of the shipwreck is

overwhelming) and of course, very effective CGI. Claudio Miranda, the DoP on

his film is plucked straight from another film with masterful

image-manipulation and CGI, another literary adaptation: 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button –

incidentally, that film featured major sequences with its protagonist stuck in the middle of a

sea-typhoon – this, perhaps, may have led to Miranda’s hiring. Pi is anticipated to sweep most of the

technical awards at the Oscars and for good reason too.

The film is supposed to be a

very faithful adaptation of the Martel’s book – one may assume therefore that

the book describes textually all these sequences of nature’s fury and

simultaneously, its immense enigma and beauty. In that, Martel’s writing is

entirely of the sort that Henry James demanded in the early 20th

century from authors when he said that contemporary literature must grow to

more visual or atleast, visually imaginable. This is an

interesting proposition, for if an author’s work is merely to describe a scene

in detail so lucid that it can be visualised

by his reader – is the job of the cinema director who then adapts this writing

not akin to a police sketch-artist, who translates a vague verbal description

by the witness into a visible, material, printable, copy-able form on the page?

Is it not his task to expand on this ambition and not undercut the abilities of

his own medium, to locate the spirit of a written passage and not its literal

meaning and then to film that? One

wonders, regardless, of how Martel’s book may have described the sequence of

the storm that wrecks the ship or the carnivorous self-devouring island near

the end – whether his words could convey the sense of immediate sorrow that

permeates the first sequence and danger that permeates the second. Maybe that in fact is the crucial feature of a

filmed sequence: its immediacy, its ability to pass one by and already be past

in the time that a reader may take to even begin composing an imagination from

the words he reads on the page.

One could, however, also think of Lee’s film

and its faithfulness to the words of Martel as being one type of adaptation - the sort where a well-known book is cautiously

chosen by a studio executive (in the case of Pi, Gabler), optioned by the studio-heads, nurtured and tended for

years at end by the property-owner because it can see potential – usually of the sort where the project will

inevitably attract major industry-talent and trade-hype. This is to say that

the moment it gets greenlit, a well-armed crew of scrawny, grown-up men will be

dispatched to some corner of the world to translate a few passages from the

book into sequences of vulgar scale and massive proportions – the sort that are

‘awe-inspiring, breathtaking and eye-popping’. And history is proof that a

studio will blow up money if it can sense an eventual extravaganza – like

bringing up a child only so that it can become the best pinch-hitter ever

known. And then there is the second sort of adaptation, one where a personality-director

himself first chances upon and then chooses a book he must adapt. This is

usually because the director can sense more than merely an opportunity to leech

on or extort from existing work –

instead, he or she may think of the book as fertile ground; as material that

facilitates a setting, a set of conditions, thematic or ideological concerns and

peculiar individuals that populate its pages – this will permit him to use the

book as some sort of a springboard for his own ideas. The book can then provide

the empty vessel which the filmmaker can fill with entirely cinematic

qualities: rhythm, mood, gestures, atmosphere, manners, quaint mood and such.

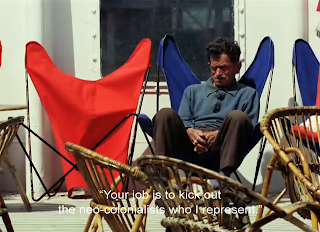

In a description

of David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis

while declaring it as the best film of this year, critic Srikanth Srinivasan

began with, ‘'Surely, it takes a bona fide auteur like David Cronenberg

to locate his signature concerns in a text – such as Don Delillo’s – that deals

with ideas hitherto unexplored by him and spin out the most exciting piece of

cinema this year.' I requested him over email to perhaps elaborate on this; he

replied, ‘Cronenberg's

cinema hasn't directly dealt with the crises of modern capitalism, which seems

to be the chief concern of Delillo’s novel…[but] it is rattling to see what

Cronenberg does here: he locates a body horror narrative within a story about

the absolute abstraction of capital.’ Needless to say, this is very interesting

– the fact that one artist’s work facilitates the other’s or at the very least,

makes it possible – it isn’t entirely a collaboration (or a collaboration at

all) but it is still a relationship of simulated synthesis – the adaptation extends the original work, confirming

that any harmonious adaptation is, atleast in one way, a living proof of the ductility

of the original work itself. Satyajit

Ray, a prolific literature-cinema translator throughout his own career (the Apu trilogy, Jana Aranya, Devi, Teen Kanya, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne among others)

wrote in his essay, ‘Notes on Filming Bibhuti Bhushan’, ‘…One can be entirely

true to the spirit of Bibhuti Bhushan, retain a large measure of his […] …

lyricism and humanism combined with a casual narrative structure – and yet

produce a legitimate work of cinema.’

However, there are other instances in the

history of cinema too where the whole adaptation business can come across as

some sort of a turf-war, with the author of the book desperately attempting to

reclaim his own work from the wrenches of a star-director who is running away

with it. This usually happens when an uptight author refuses to free his work

from the bondage of a single meaning, the one he intended – it is when the author feels that its adaptation will

interfere, or worse, tamper with the agenda of the original text that he takes

up arms. Apart from the obvious fun-times inherent in seeing two grown up dudes

trying to prove who the bigger artist is (these are always fun), this sort of

dissent also points at the infrequent inability of the two media to reconcile –

to reach some sort of a peaceful treaty.

During the shooting of The Shining, pop-culturist author Stephen King would often receive

calls at two in the night from the film’s legendary director, Stanley Kubrick.

He would pick up the phone, half-asleep and groggy: ‘Hello?’; from the other

side, Kubrick would ask, ‘Hi Stephen, do you believe in God?’ The eventual

no-love-lost relationship that Stephen and Stanley shared could be attributed

to these creepy post-midnight interferences, but King’s problems with Kubrick’s

film were greater. He said upon viewing the film, ‘I was deeply disappointed in

the end result…Not that religion

has to be involved in horror, but a visceral skeptic such as Kubrick just

couldn't grasp the sheer inhuman evil of The Overlook Hotel. So he looked,

instead, for evil in the characters and made the film into a domestic tragedy

with only vaguely supernatural overtones…it's a film by a man who thinks too

much and feels too little…’ The last bit

isn’t really a very original complaint when it comes to Kubrick; regardless, it

is of great interest that at the same time, King expressed a desire to film the

novel himself. He did, eventually. His version, released as a mini-series in

1997 was widely panned and cited as an example of a giant in one medium taking

a bite larger than he could chew. In his failure, he seemed to have vindicated

Kubrick’s understanding of how his own novel should be filmed – one must do

only what one is good at. There have been other cases too, such as when Alfred

Hitchcock quite famously declared that the book that resulted in Psycho wasn’t ‘all that good to begin

with’ or when Forrest Gump author

Winston Groom, hugely dissatisfied with the (enormously successful) Hollywood

adaptation of his 1986 novel began the sequel with a grudgy Gump telling the

readers, ‘Don’t never let nobody make a movie out of your life’s story…’

Anyways, these are all fun-and games. At any rate, ego-fights aren’t a new thing at all, with ego being the main

propeller of the history of the modern world, so it isn’t unnatural for

creators and later, propagators of an idea to develop cold feet, get insecure

and fight it out as real men do: over press conferences.

One would imagine that in this era of post-art, the

world–at-large is looking for newer ways in which to amuse itself, keep itself

stimulated and to keep the gears of civilization oiled. Technology has turned a

new era where the question isn’t about possibility as much as it is about

conviction – everything is possible, as long as someone believes in it. These

are therefore fertile conditions for a newer form to emerge, an idea that

belongs to the new world, a medium that condenses contemporary anxieties,

insecurities and agitations better than any other – perhaps in this evolution,

we may finally see a real, complete

synthesis of the cinema and the literature, two awkward friends who sometimes

agree to make public appearances together – if only for the benefit of their

patient audiences.