Sunday, March 27, 2011

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Tourneur's Scope

|

| Days of Glory (1944)/ Jacques Tourneur |

Academic interest : one of the first instances in cinema in which the bullet being fired and subsequently locating its target, i.e. the entire trajectory of the projectile, is featured in one continuous shot.

Cultural interest : the victim; the sniper in the crosshairs is aiming at someone off-screen, someone we will never know. He does not intend any harm whatsoever to the person who eventually shoots him. Such pandering of an ironic circumstance, and the foreboding sense of being 'caught unawares' are typical Tourneur tics.

Kieslowski's Documentaries

|

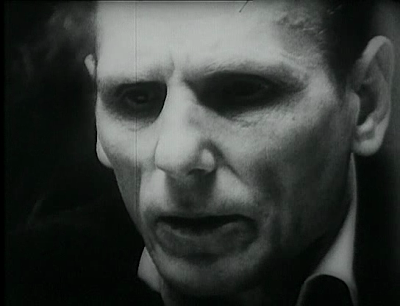

| Bylem Zanierzem(1970)/ Krystof Kieslowski |

In Bylem Zonierzem(1970), there is a much larger discourse than what you just see; or as Kielowski proves, what you merely see. The documentary, as Kielowski perceives it, is burdened with the need to ‘tell’: as such, the function of the documentary-image is information, or the Daney-image, i.e. the image as an instrument of information. But an image is, by the inherent limitations that plague it, of a wholly arbitrary nature – its only descriptive quality is strictly pictorial: what you can perceive visually, but even then, it is terribly restrictive as and so far as a tool of information. A face in a close-up is a face, a bolt is a bolt, a texture is a texture; not much else. You can clearly see the face, or the bolt, or the texture, but merely its pictorial representation devoid of its context (or text) does not tell you precisely what it is that you are seeing : whose face, which bolt, what texture. This limitation, I daresay, is all the more pronounced in the film-image (as opposed to the still frame), because a frame within a film, grabbed and posted on a blog by itself and with no larger framework to support it, is essentially nothing – just something that looks like something. As such, the capacity of information within an image is inconsequential. Kielowski’s emphasis on the documentary as a medium of information, however, forces him to look at other means beyond the image. Predictably, he looks towards text.

Bylem Zonierzem (1970) features a number of war veterans, all blinded by their participation in the event, verbally reciting their experiences of the war. Kielowski frames them all in a progressing series of extremely tight close-ups, filmed with long lenses so as to cause the visage to radiate in a sea of blur. It seems like a peculiar ploy at first, but reveals a much larger commentary on the tedium of imagery as it progresses. There are about five soldiers (seated, presumably, around a table), but because of the curious aesthetic, there seem a lot more – as one by one, they extol on the horror of war (a point the film is not interested in) and we ‘see’ them do it in an unending series of extreme close-ups. The adoption of this scheme means that Kielowski reduces the documentary film to the entrails, and exposes it for what it is : text overruling the image in an effort to ‘inform’. The film features, successively, around a hundred extreme close-ups, all similar in their magnification and image size, to the point that the image finally becomes redundant and ceases to be important anymore. At which point, Kielowski breaks the film down to a white screen with black text written on it – its opposite, ofcourse, is the most fundamental instance of the domination of the text over image.

It is ironic, but not really, that Kieslowski would turn to fiction later in his life because that seemed to make him a greater offer of truth – Kieslowki, like Kiarostami knew, that while the fiction-image is ‘truth’, the documentary-image is ‘information’.

Saturday, March 12, 2011

Notes on Black Swan

|

| Black Swan (2010) / Darren Aronofsky |

- Aronofsky has a continuing interest in the human body. But it is interest akin to Poe’s, and not to Allende’s. As such, he is not fascinated by its perfect symmetry, but intimidated by it. Therefore, it is imperative that he employ, in each film, a human body whose symmetry undergoes a devastating transformation, more or less to assume a form that Aronofsky can endear himself to more easily. Good-looking (in the traditional definition of the phrase) actors must populate an Aronofsky landscape, because it is corporeal perfection that he wages an artistic battle against. It is easy to categorise his cinema as ‘body horror’, also because he easily sacrifices metaphysics for materialism.

- No matter how profound the topic of the film, Aronofsky can only discuss it at its most literal. There is no subtext, or the image is its own subtext. Thus, Aronofsky is the filmmaker whose aesthetic is the most rooted in ‘pop culture’ – because what you see is the only artifact. If a guy abuses narcotics, he must have his arm amputated sooner or later/ if a wrestler with a condition cannot stop fighting, he will die of a heart disease eventually/ if a dancer becomes the black swan, she really will sprout wings. There is no place for philosophy in an Aronofsky film, because for Aronofsky, a film shows and philosophy is read.

- Both The Wrestler and Black Swan sprout the notion of personal art, i.e. art whose definition might be constituted differently for different people; which is to say – ‘to each his own art’. The films, however, are not about obsessive pursuit of art, but obsessive pursuit of art as a getaway route. Art as a refuge from the dreariness (in case of The Wrestler) or suppression (in case of Swan) of ‘real’ life. Both the ‘performers’ thus, treat performance as a means to escape from ‘reality’.

- There are instances in all of his films of physiognomy. There are close-ups, both in The Wrestler and in Black Swan of ‘additions’ to the human body that enhance its owner’s performance in their respective vocations – in the former, his skin gets impaled with weaponry of the primal sort; in Swan, feather follicles emerge from her scars. The ‘body’ takes precedence over all else (as point a) says), but only in Black Swan do the effects of such precedence manifest in Aronofsky’s aesthetic. There are perhaps (excluding the final on-stage performance) six long-shots in the entire film. Most of it is conducted in close-ups or mid-shots, done, presumably in long lenses. Such proximity to the human body is uncomfortable, and psychologically disorienting, because of the inherent claustrophobia of the arrangement, but also because it makes us more privy to a character’s physicality than we should be. This aesthetic is very similar to Polanski’s first, Knife in the Water, which sacrifices (like Aronofsky) any discussion of metaphysics to focus, instead, on the human body as the setting of the story.

- Black Swan is about a girl ‘transcending’ her mother’s supervision of her and growing into a fully functional adult – the moral crisis also at the heart of another very similar film, The Exorcist (Max Von Sydow does Cassel’s role in that one). The film also employs Bergman’s idea of the colour-coded morality. Ofcourse, Aronofsky’s not one for sophistication, and he is a frequent prey to his own pedantic sensibilities – so going for ‘effect’ becomes the first goal and the film suddenly becomes a horror film with much too many ‘boo-moments’. The relevance of the aforementioned Polanski-inspired aesthetic steadily dwindles as it is used in the most generic manner – because everything is in the close-up, not much of the area is accommodated. Which in turn means, there is a lot to hide; as soon as the camera pans, something new enters the frame, accompanied by a loud swoosh – alas, a ‘boo-moment’. Aronofsky can’t but help induce a lot of this nonsense into the film.

- Regardless, Aronofsky really is ‘dark’. He was slated to reboot the Batman series. If he had, we would’ve probably been ashamed of how easily we term Nolan’s comic-book accomplishment ‘dark’. Aronofsky would really have made Batman dark. He would’ve shown how it is really done; which is why the studios would never really let him do it.

Black

"Black is a color that is man-made. It is really a projection of the brain. It is a mind color. It is intangible. It is practical. It works 24 hours a day. In the morning or afternoon, you can dress in tweed, but in the evening, you look like a professor who escaped from college. Everything else has connotations that are different, but black is good for everything."

- Massimo Vignelli

Friday, March 11, 2011

The Eternal Damnation

|

| The Asphalt Jungle (1950)/ John Huston |

At their most vital, Huston’s films are about the nature of ambition. His is a conservative view of it: he looks at ambition as a fallacious occurrence, and at his most vindictive, as an act worthy of condemnation. Huston seems to believe that each man has been pre-assigned a role, and that it is imperative that he honour the demands the role makes out of him. It is the approach of a right-winger, also of a Catholic conservative; which is strange because Huston’s approach to cinematic form is that of a noninterventionist. His ‘aesthetic’ is defined by a lack of one, because as it stands, his body of work features films that are directed by a free-hand, a liberal artist. As such, his what is always at loggerheads with his how. Huston applies a radical aesthetic to conservative matter. No film of his is more symptomatic of such contempt for unhealthy ambition than his best, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, but then again, one could argue that Bogart always had it coming. He deserved it, and the shock-ending to his character was justifiable moral retribution. In his latter film, The Asphalt Jungle, however, no character deserved their eventual fate – most of them only victims of circumstance, or as Huston would have it, victims of man’s worst vice – ambition (interchangeable in a Huston film with desire). Hayden’s character Dix Handley has only one sole ambition – that to resettle in his backwater hometown and lead a quiet life – and it comes under strict Hustonian ridicule. He is supposed to lead an entire life as a low-life, a peddler on the streets of the city, with no hope of either quite or a life, and thus, such violation of the rules set by his supposed role can onlylead to stern punishment in a Huston film. He is what Tully in Fat City is, or Johnny Rocco in Key Largo is – men who are victims of their own ambition.

Friday, March 4, 2011

The Performer

|

| Outrage (2009)/ Kitano Takeshi |

Kitano is sometimes a circus comedian, sometimes a yakuza gangster. The eventual ambitions of the two vocations vary a great deal: the first makes people laugh, the second kills them. But the method(s) they employ to reach that end are very similar – both of them are primal, direct and confrontational. The practitioners of circus-comedy or yakuza-crime don’t precisely employ subtlety; the success of their performance depends on how much they overwhelm their audiences. As such, there is an element of the bizarre in both, of a certain type of outlandishness that can bludgeon its receiver into submission. Both are also marked by a pressing need to project a particular effortlessness in their performance, regardless of how strictly they have to adhere to a specific list of rituals to sustain the vitality of their performance. It is in these zones of overlapping between crime and comedy that Kitano’s filmography lies. A lot of viewers misunderstand him as a director of unrestrained violence, but that’s only a critical cliché, and one that obscures more than it reveals. He is essentially a director of performance, and as such, likes to put on a show all the time. Therefore, much like anyone else with a thing for showiness ( like the comedienne or the criminal), his first target is to elicit a response; he doesn’t care if it is a loud guffaw or an extended grimace as long as he provokes some sort of a reaction. He is vulgar, because he is gunning straight for the most pedantic of human tendencies, i.e. to enjoy humour or perversely, enjoy violence. In Outrage, violence is funny precisely because it is so exaggerated. It assumes the form of a vaudevillian, Grand Guignol performance – with chopsticks piercing ear-cavities, dental drills ravaging through disagreeable mouths and necks getting snapped. Like the circus comedian or the yakuza gangster, Kitano’s idea of cinema is to batter the audience into immediate capitulation, even while feigning decency through it all. Therefore, the images of a Kitano film are always very strong and provocative, and all of them pass by with great urgency (even when characters stand on beaches, they await a shootout). Which is why, Takeshi’s is the most prototypical Kitano film (imagery at varying levels of vulgarity) that passes by quickly, and Zatoichi (except the ending) is the least. With Kitano, crime and comedy are no longer acts of any implicit moral value – so there is no immediately evident difference between killing people and making them laugh. Both are just performances, meant to be carried out at amplified levels of intensity. Outrage is actually the best Kitano film title, because it so briefly sums up what each Kitano film is. Crime and comedy are interchangeable quantities in a Kitano film, because he shoots his crime like others shoot their comedy, and he shoots his comedy like others shoot their crime.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)